Read our latest: The year so far & 1.0 update.

Most web app development environments and toolsets treat an app as a bunch of files. The files are initially created using scaffolding tools like Yeoman and then built and deployed with the likes of Grunt, Gulp and Broccoli. These stitch together tools such as file-watchers, CSS compilers, JavaScript compressors like Uglify/Closure etc. BladeRunnerJS takes a different approach - implementing a rich domain model for a web app.

Most web app development environments and toolsets treat an app as a bunch of files. The files are initially created using scaffolding tools like Yeoman and then built and deployed with the likes of Grunt, Gulp and Broccoli. These stitch together tools such as file-watchers, CSS compilers, JavaScript compressors like Uglify/Closure etc. BladeRunnerJS takes a different approach - implementing a rich domain model for a web app.

Amidst the daily bustle of building web apps its easy to forget that things like DOM elements, HTTP requests, closures, files etc don't really exist. They are abstractions - logical constructs used to encapsulate the myriad complexities of modern computers and communications networks. What really exists are: electrons moving through semiconductors, photons passing along optical fibers, liquid crystals changing orientation when a current is applied and such-like. Our day-to-day work is only made practically possible precisely because we don't have to think about the details of such things. The bulk of computer science is about building layers of abstractions. Good abstractions make programmers hugely more productive, giving us the mental models to think, communicate and solve problems effectively.

If abstractions are so important, what is a good way to model a web app? For BRJS we've decided to create a fully fledged domain model. Rather than try to describe the whole thing, a few examples will hopefully give a flavour of our approach. Each application is modelled as an instance of the App class. The bulk of an App's code is contained in isolated features (components) called Blades.

To list blades in an App simply execute the following code:

BRJS.app("my-app").bladeset("my-bladeset").blades();

A BladeSet is a mechanism for grouping blades. In turn a Blade consists of many Assets each of which represents a single resource like an image, CSS or JavaScript file.

The Blade is responsible for knowing where Asset files may live on disk. Every (sub)type of Asset must implement the following interface:

public interface Asset {

Reader getReader() throws IOException;

String getAssetPath();

String getAssetName();

...

}

As you can infer from the interface, Assets are responsible for transforming their input into a readable stream (e.g. compiling CoffeeScript to JavaScript). They also provide string names (decoupled from their location on disk) by which they can be referenced.

A LinkedAsset is a subtype of Asset which also provides the list of other Assets it depends on. JavaScript code can define dependencies using require statements. However LinkedAsset implementations are free to calculate dependencies any way they like e.g. using regular expressions.

Unlike most tools BRJS doesn't have to parse and load JavaScript to calculate dependencies. We can therefore treat HTML and JSON (and other configuration formats like XML) as LinkedAssets that have dependencies.

BRJS performs a recursive analysis and models your app as a full dependency tree rooted on its index page. This enables BRJS to deliver the minimal code to your browser and provide a dependency analysis tool.

$ ./brjs app-deps myApp

Aspect 'default' dependencies found:

+--- 'default-aspect/index.html' (seed file)

| \--- 'myApp/Class1'

| | \--- 'myApp/Class2'

| | | \--- 'myapp/Class3'

| \--- 'myApp/Class2' (*)

| \--- 'myApp/Class4'

(*) - dependencies omitted (listed previously)

The full domain model also includes classes that represent tests, minifiers, deployable artifacts etc. In short it fully understands the semantics and (dependency) structure of your web-app. It's not just a bunch of files but a rich model that is decoupled from the actual structure and contents on disk (also see Bundlers).

The model deals with abstract concepts like Assets, LinkedAssets and Blades defined using interfaces (contracts). Plugins provide actual concrete implementations (that conform to the specific interface). They generally have all or part of the BRJS model passed to them which they query and/or update.

BRJS contains a working set of plugins. For example we have NodeJsAssetPlugin and NamespacedJsAssetPlugin implementations. The NamespacedJsAssetPlugin supports a legacy style of JavaScript that we use in Caplin. The plugin mechanism allows us to interoperate both code styles. In the near future we will be adding a plugin for ES6 style JavaScript.

The bulk of the BRJS codebase consists of plugin implementations and it is a simple matter to add new ones.

It is instructive to compare this approach to that taken by current build tools. This article by Jo Liss, the author of Broccoli, is a really great analysis of issues.

Summarizing the JavaScript tools:

Like Jo we believe that to maximize developer productivity you must minimize the time from changing a line of code to reloading the browser. BRJS is primarily aimed at very large apps so we must have a scalable solution. Our domain model is responsible for watching all our Asset files. The model methods cache their results, which are only recalculated if some inputs change (see memoization).

Where we part company from Broccoli is that we believe web developers should think in terms of HTML, CSS, JavaScript, tests, minifiers etc not files. Files are a lower level (more generic) abstraction. Our tools should reflect developers mental models - this is one of the core reasons we chose a domain model approach.

This enables us to reason about a web app and aids communication between developers. Although the most nebulous advantage it is also in many ways the most important.

Many plugins are provided as part of core BRJS but it is easy to add new ones. Rather than just being able to look at files, plugins access the domain model.

The dependency analysis plugin uses the dependency model (which is a graph) to generate the output shown above. Similarly we just created a plugin that automatically creates an application cache for a mobile project. It consisted of a few hundred lines of code - querying the domain model and generating the .appcache file.

This reduces the cycle time from changing a line of code to reloading the browser - essential for good developer productivity. Even better, memoization is hidden inside the model so plugin developers reap the rewards without even being aware its happening.

The JavaScript development ecosystem is changing very rapidly e.g. ES6 and Web Components will be available shortly. The code and structure of an app built today is radically different from one built three years ago. Large scale applications however are long lived and we can't afford to be constantly re-writing them. The plugin architecture and model allow us to keep legacy code running and interoperate with newer styles of code and tooling. This gives us a smooth migration path as web technologies emerge.

With many developers working on a web app it helps to have consistency across the codebase. The model allows the enforcement of conventions. For example, the domain model (through namespacing) ensures that developers on separate areas of code cannot cause conflict by using duplicate HTML ID's or i18n labels.

Because all the conventions and tools are encapsulated within the model (and core plugins) it is easy to onboard developers quickly. They don't have to spend time setting up build config files and installing build dependencies. They put code in the conventional place and refresh their browser - after having run their tests of course!

The great thing about having all your conventions encapsulated in a single place is that if you don't like them they are relatively easy to change.

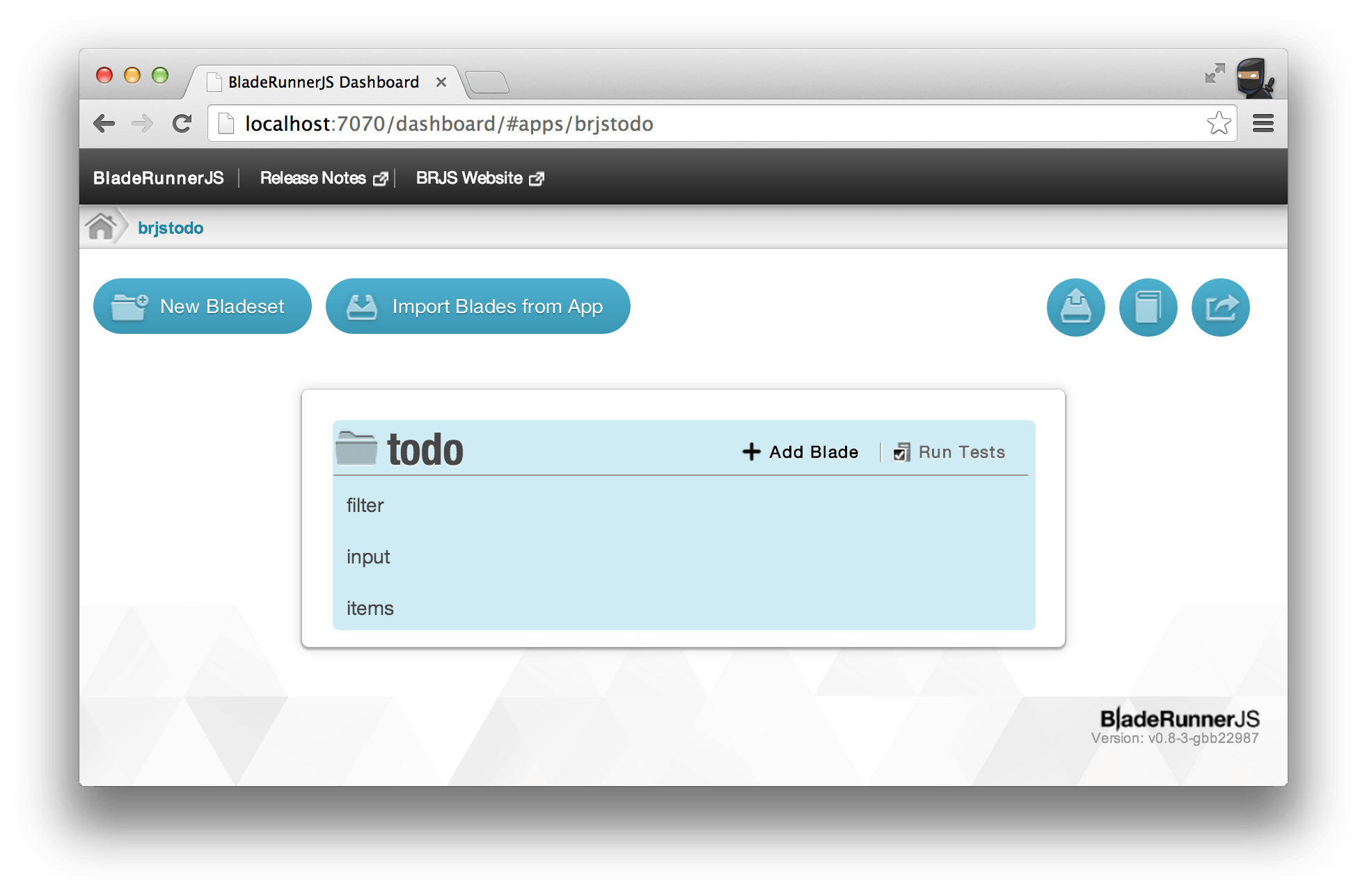

For example our BRJS "Dashboard" allows you to browse a visual representation of your web app.

You can explore, run tests, scaffold new Assets and build the final deployment artifact with the click of a button. It works by calling a web service layer that interrogates the domain model.

At Caplin we've already reaped the benefits of using a domain model rather than just treating everything as files. Although remember that the concept of a file is one of the most successful abstractions used in computing. Without them we'd be thinking about spinning magnetic disks!

Many thanks to Phil Leggetter and Dom Chambers for their feedback.