Read our latest: The year so far & 1.0 update.

One of the great things about open sourcing a product is that you are opening up what may previously have been seen as a black box. With all the source code freely available, anybody can take a peek inside. However, that can still be a big task, especially with a large codebase. So I thought I'd write up a mini guided tour and provide a few details about what you'll find inside the BladeRunnerJS (BRJS) gift wrapping.

One of the great things about open sourcing a product is that you are opening up what may previously have been seen as a black box. With all the source code freely available, anybody can take a peek inside. However, that can still be a big task, especially with a large codebase. So I thought I'd write up a mini guided tour and provide a few details about what you'll find inside the BladeRunnerJS (BRJS) gift wrapping.

With so many developer toolkits and libraries to choose from when starting to build a front-end JavaScript application, it can be difficult to know where to start. Combine with that the need to define a workflow to follow during the development process, how to ensure team members and different teams across an organisation can work on the same codebase without stepping on each others toes, how to integrate with a CI (Continuous Integration) solution and how to deploy; the choices can get even more complicated.

We had exactly these problems, and our customers had them too when they took our older JavaScript SDK to build their own complex front-end web application. BRJS represents the solution to these problems; a developer toolkit that enables, encourages and enforces a scalable workflow and application architecture, combined with a number of key components required when building a complex front-end web application that will scale. And by "Scale" we mean meet the demands of building a functionally complex application that allows multiple teams to work simultaneously on a codebase belonging to that same app.

BRJS is fundamentally a product that integrates a set of tools and libraries that has meant our development teams, and those of our customers, can focus on writing feature code and not on setting up and configuring a development environment; the first line of code you write when using BRJS is feature code (or a test that drives a feature if you follow TDD).

So, what tools and libraries have we chosen, and why? And how are we handling the fact there may be (well, are) cases where better tools or libraries come along?

Below is a high-level diagram showing the parts within the BRJS toolkit and runtime.

Now, let's go into more detail about each part:

Let's first take a look at the BRJS toolkit; the tooling that supports development and the development workflow:

The first question many may ask is why Java and why not Node.js? James Turner recently wrote about how we plan to embrace Node.js covering the reasons and our future considerations.

My summary would be:

Our eye is most definitely on Node.js and we are looking at integrating with some of the fantastic tools and libraries that are available right now. We may move the toolkit to Node.js in the future, or we may staying with Java and take advantages of the upcoming enhancements and technologies.

See James' post for more details.

You use the BRJS CLI (Command Line Interface) to perform common tasks such as start the development web server, create applications, create blades or run tests. It's likely to be the point of interaction to most toolkit actions.

You also use the CLI to access any CommandPlugins that you've added. You can get a full list of available commands by executing brjs help.

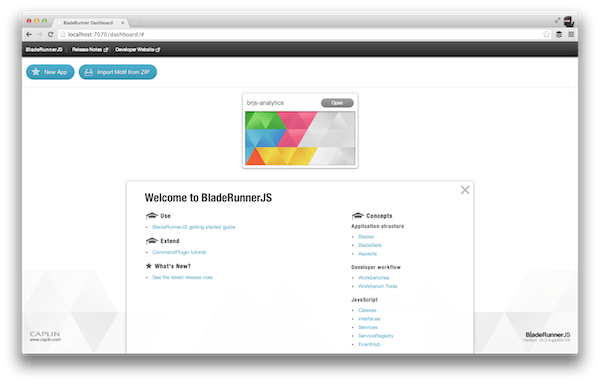

Not everybody likes the command line or terminal. And for some tasks a GUI can actually be pretty handy. BRJS comes with a web dashboard, accessed via http://localhost:7070, that provides a way of navigating applications and executing common tasks like creating apps and blades. This is a feature we're interested in getting feedback on and seeing if it's something that gets a lot of use and deserves more attention.

When running a web application it's best to do so from a web server as it better reflects the production runtime. BRJS contains Jetty as the development web server which is relatively small, was easy to embed in the BRJS toolkit and we also get the ability to do things like add new contexts programmatically when applications are created.

In the development runtime environment BRJS servlets handle the mapping of requests to the appropriate resources, enabling integration with other tools such as bundlers.

In the development runtime JS, HTML, CSS and other assets can be optionally bundled and minified (JS only minification right now). The deployment packages contain bundled and minified resources by default.

The toolkit provides an export command which creates a deployment package for your target production environment; right now WAR and soon Flat File. The BRJS plugin architecture allows custom deployment environments to be targeted.

As above, BRJS comes with a JavaScript compiler and minifier. We use the Closure Compiler for this as it's a proven tool, is actively developed and used by Google in products like Gmail, Google Maps and Google Docs.

Before we feed our JavaScript into Closure, we first do our own bundling. We do this aided by our own dependency analysis functionality that is provided by the default BRJS bundler plugins.

As above, we have a JavaScript Dependency Analyzer as part of the toolkit. This allows us to understand the code that is being used. We can use this in our tooling and when bundling JavaScript to ensure that only classes that are actually used are included in the payload to the development server and in bundled production assets.

The first JavaScript bundler plugin that we are just about to release will support Node.js/CommonJS style modules that can be used within the web browser. This is backed by the dependency analyzer that understands the require syntax and a JavaScript Module Loader that facilitates the declaration and retrieval of modules (see the "Modular JavaScript" section below for more details).

We have our own fork of JS Test Driver that makes up part of the BRJS toolkit. We chose to use it around two years ago (in place of JSUnit) because it made debugging much easier, it didn't require an HTML wrapper and it increased the speed at which we could run our tests (e.g. running tests in parallel in different browsers). It also enables both unit and acceptance tests to be run in our environment.

We're presently looking at Karma integration because it’s flexibile, has the same benefits as JSTD, and is getting much more love at the moment.

Karma also fits in easily with the BRJS plugin architecture and it has a plugin architecture all of it’s own. It is a test-runner, so BRJS can use it to run any existing tests (providing backwards compatibility), and it can be used to run tests using alternative tools, or even tools that don’t exist yet. It also provides the kind of flexibility that we're looking for to all BRJS users; you can use an alternative test framework by writing either a BRJS plugin and/or a karma plugin.

In addition, we have heard that Karma interacts with browsers in a more efficient way than JSTD, providing a more reliable interface over which tests will run. Karma demonstrates how Node.js based testing tools can become part of the overall BRJS tool chain, by the simple addition of a suitable BRJS Command plugin.

With the toolkit covered we can now take a look at what's provided as part of the BRJS front-end application runtime.

As much as possible the JavaScript application framework is built up using micro-libraries. The aim here is to provide a solid foundation upon which you can build your front-end application. But, it also means that if required you can choose not to use some of the higher-level libraries and instead use your own preferred libraries.

When we started off the open sourcing project one of the main changes we wanted to make was to our our coding style and how we defined our code modules; it was functional, enabled our developer workflow, but was highly verbose.

We decided upon a pluggable solution, with our first supported coding style being Node.js/commonjs. To support this we needed an implementation of require that works in the browser and integrated with our bundler. There are other implementations of require - e.g. browserify, but they don’t integrate with our bundler. Because browserify is so modular, we were able to reuse parts of it's code easily and just modify the generated code.

The module loader provides a define(module_id, module_definition_function) and a require(possibly_relative_module_id) function. It supports some extra features too, but we'll cover our module loader in more detai in a separate blog post in the future.

One thing to note is that you don't have to use the define function in your code and wrap your module definitions in a closure (as you do with RequireJS), the JavaScript bundling process automatically injects this as part of the build process. This means that you can focus on writing code focused on providing application functionality and not writing code to work around the runtime environment.

Our module loader can be found on github here.

JavaScript is a prototypical language and doesn't natively support classical inheritance, or provide support for some important OO concepts such as Interfaces. We believe that when building a quality scalable software applications, classical OO is a great approach. So, we've created a library called Topiarist that enables us to do this.

For more information please see the Topiarist blog post.

For applications to effectively scale their architecture need to be modular: constructed of pieces of functionality that can be easily tested and where the underlying implementation of certain parts of the application can change without impacting the application as a whole.

The concept of Blades achieves this, but BRJS applications also have two further concepts that help, both of which can be driven by simple configuration (code setup or config files).

The first is through the use of services to configure a single canonical instance of a class that fulfulls a service promised by an Interface e.g. a LoggingService where the intial implementation may log to console.log but a later implementation also sends log messages to a back-end web service.

The second is through a concept called aliases to allow you to refer to JavaScript classnames using name-spaced logical identifiers so the underlying classes that are instantiated can easily be configured. This is particularly useful for our bundling process as aliasing is used in JavaScript, HTML, CSS and more.

The ServiceRegistry and AliasRegistry core JavaScript libraries are particularly useful because it lets you write generic code that will work in new environments, and the classic usage for us is in tests where we can switch out real services for mock or dummy implementations.

We wanted to use an existing emitter library, but couldn’t find any that were:

emitter.on( 'some-event',

function() { /* callback */ },

this /* context */ );

Also, since our normal use case is for our callbacks to be methods on objects and not anonymous functions, not having the latter capability adds significant overhead in making sure that you clean up after yourself.

Emitr is used by a number of our BRJS libraries, including the EventHub which is available as part of the default BRJS application runtime.

The Emitr library can be found on github here.

There are a million JavaScript logging frameworks and there was no way we could have evaluated all of them. So, we took what seemed to be the 10 most popular ones and evaluated them. In the end we decided that most of them did too much. We wanted one focussed on being friendly to testing and highly performant in the case that you don’t actually need to do anything with the message - which is probably 95% of the time.

The Fell JavaScript logging library has been open sourced and is available on github here.

When building applications for users all over the world internationalisation and localisation is highly important. The BRJS toolkit allows internationalised versions of your app to be built by performing static tag replacement.

I decided to put this in the JavaScript framework section as JavaScript calls are also used to apply local languages, and using local date and number formats for display and data-entry. i18n is thus a cross-cutting-concern, from toolkit built process to application runtime.

It's nearly universally agreed that a MV* is a good approach when building a front-end application. We chose to go with MVVM (Model-View View-Model).

The great thing about MVVM is that it works particularly well with data-binding. The View Model is a logical representation of the View so when you update the View Model you simply need to ensure that the View is updated to reflect the View Model state. In our financial applications, we tend to use a dedicated library to handle this called Presenter which we built on top of the excellent KnockoutJS. In some applications we may use plain KnockoutJS.

The game-changer here was that it allowed us to migrate a large number of selenium tests, which relied on checking DOM state, to tests that tested the View Model instead. This massively increased both the reliablity and speed of the tests. Combining this with the use of Services meant we could test the functionality offered by a Blade in isolation; from View Model to service interaction and service interaction through to the affect that would have on the View Model.

This resulted in changing the runtime for our full test suite from 8 hours on a VM farm, and being unreliable, to 10 minutes on a single machine, and highly reliable. This is worth of a blog post all on it's own.

In the sections about JS Test Driver, the Module Loader and IoC/Dependency Injection I mentioned "change". When building a complex application it's important to identify the components that may change and add abstractions around them so the implementations can be swapped out. In the case of a BRJS application those components will probably end up as services accessed via the ServiceRegistry. When building BRJS we've had to think about what things may change in the future and how we can facilitate and enable that change.

As above, as much as possible we're moving to making the BRJS application runtime consist of micro-libraries that don't have any direct dependencies on other parts of the default application runtime. And where there are dependencies, those should be on interfaces and not concrete implementations.

We've approached the toolkit in the same way and we've created a plugin architecture that will allow us to switch out the implementation of things like test, bundling, minification and content replacement.

I'm particularly excited about the JavaScript bundler. Right now we're going to support commonjs/Node.js style modules and code. But, because this is handled through a plugin architecture there's no reason why we could support CoffeeScript, TypeScript or ECMAScript 6 in the future.

When you unwrap BladeRunnerJS you'll find a base application runtime and structure that provides the foundation for building complex front-end applications across multiple teams. Additional runtime components are optionally accessible to further ensure that your application will scale as it is built.

The toolkit is also built in a way that offers a base level of functionality along with a set of default plugins that can be used used for a highly productive developer workflow. This can be augmented as required as your workflow evolves.

All this means when you start off with BRJS and use the default set of libraries and toolkit plugins that your first line of code can be feature code. But it also means that you are given the power to change both the developer workflow that the toolkit provides, and the application runtime, as development progresses or as new libraries and tools become available.

For those reading this during the festive season, Happy Holidays!